There’s something disheartening about reading two people argue over what’s wrong with contemporary art and realizing neither of them really cares to say what art is for. That was my experience reading Dean Kissick’s “The Painted Protest” in Harper’s and Ajay Kurian’s rebuttal in Cultured. Both essays circle around identity politics. Kissick blames identity politics for destroying contemporary art, while Kurian defends it as a necessary corrective. However, neither writer tells us, or even really hints at, what art is meant to do. I mean, you should clarify what’s being destroy, or defended. Shouldn’t you? Why art matters in the first place. Why would anyone, in a world like this, risk their life on a photograph or a song or a sculpture? And you know, people do.

Kissick opens with a brutal story: his mother loses both legs in an accident on the way to what is basically a textile art show. It’s a horrifying opening. You wonder, is this made up? It can’t possibly be real. But the story goes nowhere. It becomes a kind of emotional pyrotechnic that as far as I can tell doesn’t connect with anything else in the piece. He never really returns to it. He doesn’t mine it for meaning. He just moves on to declare, more or less, that contemporary art is boring. That Art’s become a series of therapeutic gestures masquerading as political clarity. That everything looks the same, sounds the same, feels the same. He wants art to be strange again. Transgressive again. He say he misses beauty.

He’s not wrong about that feeling. Many of us have walked through shows that feel like checklists: here’s the trauma, here’s the wall text, here’s the identity framework. There’s nothing to argue with, and very little to feel. The art isn’t bad, exactly, it’s just thin. Like frozen grape juice you find out is really grape drink! It doesn’t surprise. It doesn’t risk failure. It tells you what to think and then congratulates you for thinking it. Personally, I have trouble going to MFA shows these days because I feel like the unsuspecting family member who is tricked into family therapy. I never leave happy. Yes, a lot of the work is about identity politics…but the problem is it’s often just bad art.

Kurian, to his credit, brings receipts to the table. He reminds us that identity didn’t enter the art world by accident; it got here by force, by necessity. Museums and galleries were exclusionary for centuries. For artists from historically marginalized groups, the act of simply showing up was, and often still is, radical. Kurian is right to call out the reactionary tone in Kissick’s essay, that strange yearning for a time when things were more mysterious, more “pure.” He reminds us that purity in art almost always meant whiteness, money, and control. Personally, I just don’t need to be reminded so often. (I am a doctor, specializing in neuropsych assessments and have met patients at Costco who, after meeting my partner, never come to another appointment. Guess why.)

But what Kurian doesn’t do is push the argument forward. He defends access, but not vision. He talks about power, not presence. He names the historical violence, but he doesn’t ask what art is for now, now that more people are finally in the room. Hey, we are all here. So now we are all in the room, what are we going to do? What have you got to say? How are you going to say it?

I’m less interested in whether identity politics have saved or ruined art, and more interested in what gets lost when art becomes about me instead of us. Maybe that's because of a few extra decades on my calendar. It’s not that I’m apolitical. Here is a list of the political campaigns I was involved in: Kennedy in 72 (sorry. I was in High School!), Eugene McCarthy for President (we were not kidding!), George McGovern, Moe Udall, and finally Jerry Brown for President, twice. Lesson: Don’t let me into your campaign headquarters; things will likely not go well. Oh, and I was there when Larry Kramer called ACT-UP together…and after a bit of frustration, at the start of Queer Nation and the campaign for marriage rights. So, I am no stranger to politics, making political statements, protesting, writing political news stories or political organizing. Just want to make sure no one mistakes me for someone else!

Back to the story at hand: Both writers treat art like a battleground for political symbolism, but neither of them seems interested in what happens when someone actually stands in front of a work of art and feels something real. They never talk about how a photograph can shake a person, or how a painting can change the room you walk into. Nothing like that. There seems to be no art talk left

(photo: Untitled Vietnam War Protester, Judith Joy Ross)

That’s what I see in the work of artists like Judith Joy Ross. Look at her photos….seem a little conventional? Well, read her, or listen to interviews. She is deeply political, and anyone who’s listened to her speak knows how much emotional effort it takes to make her portraits. She photographs children in public schools, veterans at the Vietnam Memorial, strangers at polling places. The images are charged, ethically resonant, but never solipsistic. They are about the people she stands in front of. She’s not hiding her politics; she’s simply not letting them smother the image. The images, as conventional as they may look at first punch you in the gut.

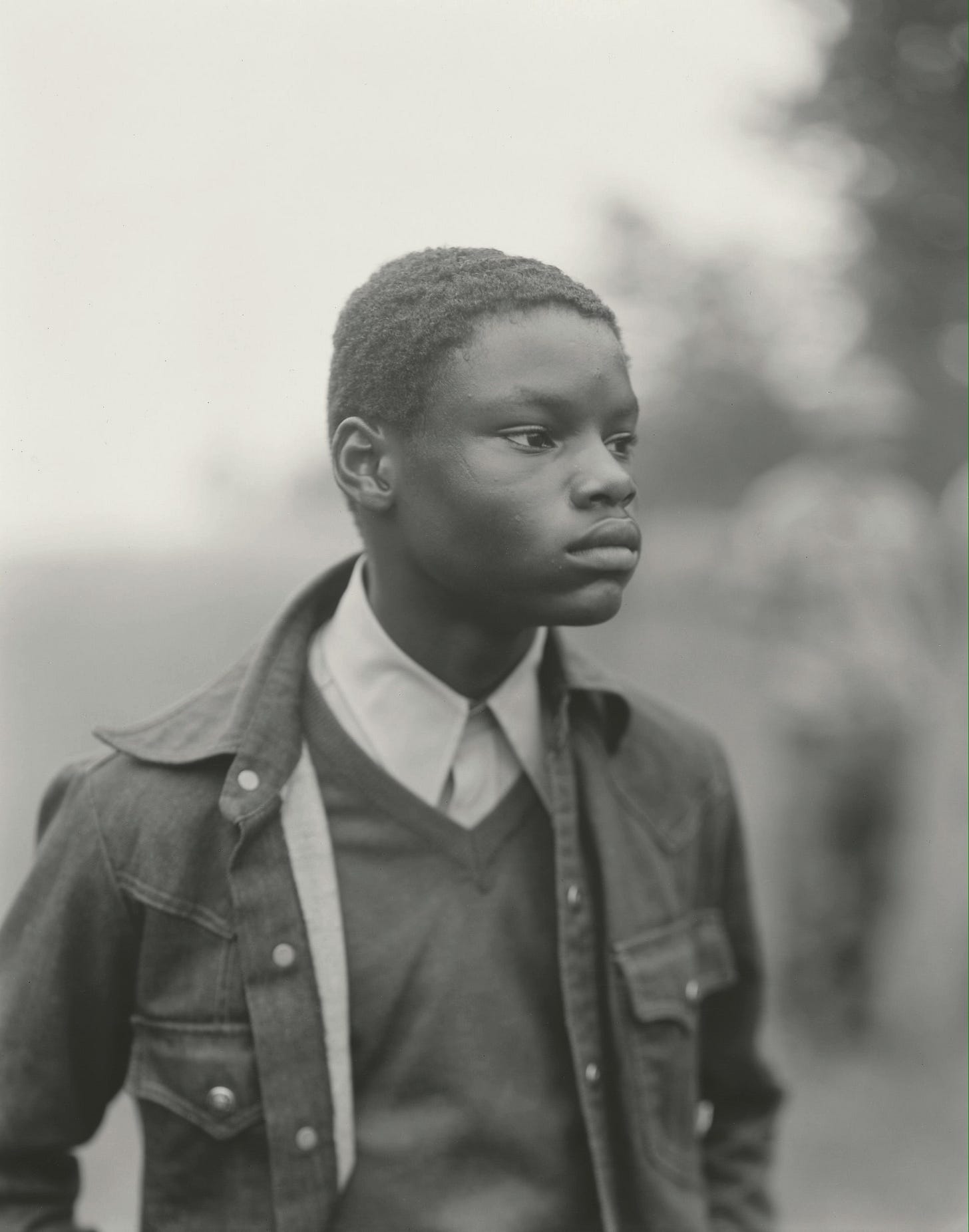

(Boy at the Vietnam Memorial, Judith Joy Ross)

Seek out her portrait Untitled Girl with plaid skirt, Hazleton Public School, Hazleton, Pennsylvania), the expression is ambiguous, dignified, open. Or her Untitled Boy at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, a child leaning against a name-covered wall, both of them seeming to absorb history. Neither is illustrative. Neither is explanatory. They simply are.

You can check more out here: Aperture](https://aperture.org/editorial/judith-joy-ross-hazleton-school-portraits/, New Yorke (https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/a-portrait-of-a-school),Yale Art Gallery https://artgallery.yale.edu/video/judith-joy-ross-artist-talk

There’s a line between making art that’s about yourself and making art that begins with you but expands outward. So much of what’s presented now as political art is really confessional, therapeutic rather than aesthetic. But art isn’t therapy. Or if it is, it’s therapy for the species, not the individual. The problem that has nearly destroyed the world, or may have already, is the problem of me, me, me.

These works are first and foremost bautiful. Beauty is the language we use to talk to strangers. That’s what both Kissick and Kurian miss seem to miss. Beauty, not prettiness, but the moment of recognition, of clarity, of form and feeling aligned. This is how art does its work. Not by arguing. Not by explaining. But by connecting.

That’s what Dave Hickey believed. Hickey wrote like a man possessed (by jazz they say), by pornography, by rock and roll, and by painting. He wasn’t afraid to sound outrageous because he wasn’t trying to win a committee vote. He wanted art to be free, to be democratic. In Air Guitar, he writes: “Bad taste is real taste, of course, and good taste is the residue of someone else's privilege.” For Hickey, beauty was dangerous because it didn’t follow the rules. It seduced. It convinced. It reached across difference without erasing it.

But beauty wasn’t optional either. In The Invisible Dragon, Hickey makes a radical claim: that without beauty, art can’t function. “Without the ability to measure desire, we are at a loss to understand our humanity,” he writes. That was Hickey’s mission: to defend art’s ability to move, to provoke, to charm.

Elaine Scarry, in On Beauty and Being Just, echoes this, writing that beauty “brings copies of itself into being.” It asks to be shared, shown, replicated. Beauty is not a private property, it’s an invitation.

Robert Adams, on the other hand, would never use a phrase like that. He doesn’t seduce, he “clarifies.” His books Why People Photograph, Art Can Help, and Silence, read like moral testaments, but without sermonizing. He believes, stubbornly, that photography can help us see what’s good and still possible. In Art Can Help, he writes, “In our time, perhaps the most redeeming feature of art is its unimportance.” That line stops me every time. He means: art can tell the truth because it’s not enslaved to usefulness. Because it doesn’t have to win. Too much of what I read is about winning.

In Silence, Adams photographs light falling on sidewalks, the edges of buildings, trees and utility poles. But it’s never just formal, it’s always, as he writes, ethical. What do we allow ourselves to see? What do we learn to ignore? These are ethical questions. He believes that what we notice is what we come to care about. His art is an act of attention, which becomes, quietly, an act of love.

See: Longmont, Colorado from The New West or Colorado Springs from Summer Nights, Walking—both available through [Fraenkel Gallery](https://fraenkelgallery.com/artists/robert-adams) or the [Yale University Art Gallery](https://artgallery.yale.edu/).

If Hickey is all heat and seduction, Robert Adams is winter light through frosted glass. But they share something rare: they both knew what art was for. Not politics. That’s advertising and design. Not the market. Not self-expression. Art is for connection. It’s for seeing what we didn’t know we needed to see. It’s for reaching someone else, without knowing if they’ll agree, without knowing if they’ll clap or click.

And that’s why this argument about identity politics, as it currently stands, feels so empty. It’s not that identity doesn’t matter. It’s that we’ve made it do all the work. Identity has become the content, the form, the justification, the context, the politics, and the press release. It’s too much weight. No image can carry that alone.

What artists like Ross, Adams, and Hickey (besides being a critic, Hickey had a life as a songwriter) remind us is that identity is a starting point, not the point. The best art doesn’t insist on being seen. It lets you see. It opens a door. It doesn’t trap you in the artist’s life; it hands you back your own.

I still believe in that kind of art. The kind that changes the air around you. That leaves you quieter than before. The kind that you carry home without meaning to.

Kissick wants art to be wild again. Kurian wants it to be just. I want it to be true. I want it to remember what it’s for. Because if art isn’t about helping us live with strangers, then what is?

---

Where to Start

Robert Adams: Why People Photograph (1994) – personal essays on photography as ethical attention; Art Can Help (2017) – slim, elegant, and essential; Silence (2020) meditations on seeing, quiet, and survival

Yale University Art Gallery (https://artgallery.yale.edu/) | [Fraenkel Gallery](https://fraenkelgallery.com/artists/robert-adams)

Dave Hickey: Air Guitar: Essays on Art & Democracy (1997) wild and essential The Invisible Dragon (1993/2012) four essays on beauty, risk, and censorship. Also read his Mapplethorpe essays and Pagan America

Judith Joy Ross: Judith Joy Ross: Photographs 1978–2015 (DelMonico/Prestel, 2022), Aperture: School Portraits (https://aperture.org/editorial/judith-joy-ross-hazleton-school-portraits/) Yale Art Gallery Artist Talk (https://artgallery.yale.edu/video/judith-joy-ross-artist-talk)

Elaine Scarry

On Beauty and Being Just (Princeton, 1999) a philosophical defence of beauty as a form of ethical fairness

Copyright & Fair Use Disclaimer

Some images and artworks reproduced in my writing are the copyrighted property of their respective artists, photographers, estates, or institutions. They are included here solely for the purposes of critical commentary, educational discussion, research, and scholarship. This use is protected under:

United States Fair Use (Section 107)

Canada’s Fair Dealing (Copyright Act, Sections 29–30)

United Kingdom Fair Dealing (CDPA 1988, Section 30)

If you are a rights holder and believe your work has been used beyond fair use or fair dealing, please contact me. I will remove it promptly upon request.

You can help most by reposting this essay.

I empathise with much of this although, thankfully, I don’t see much art that is dominated by identity politics. There’s an interesting tension in your argument that proposes art as both useless (without purpose or utility) and useful (ethically, aesthetically, socially). I like Gert Biesta’s notion that (in the context of education) art’s value is in its ability to stage an encounter with reality and provide an experience of resistance. I’m less bothered about what happens in the world of professional artists and galleries - the art market - which is merely a symptom of global capitalism (and definitely about a few winners). Your comments about ethics are very helpful and astute. Thanks again for a super thoughtful and heartfelt post. I so look forward to reading them.

A brilliant piece Jim.