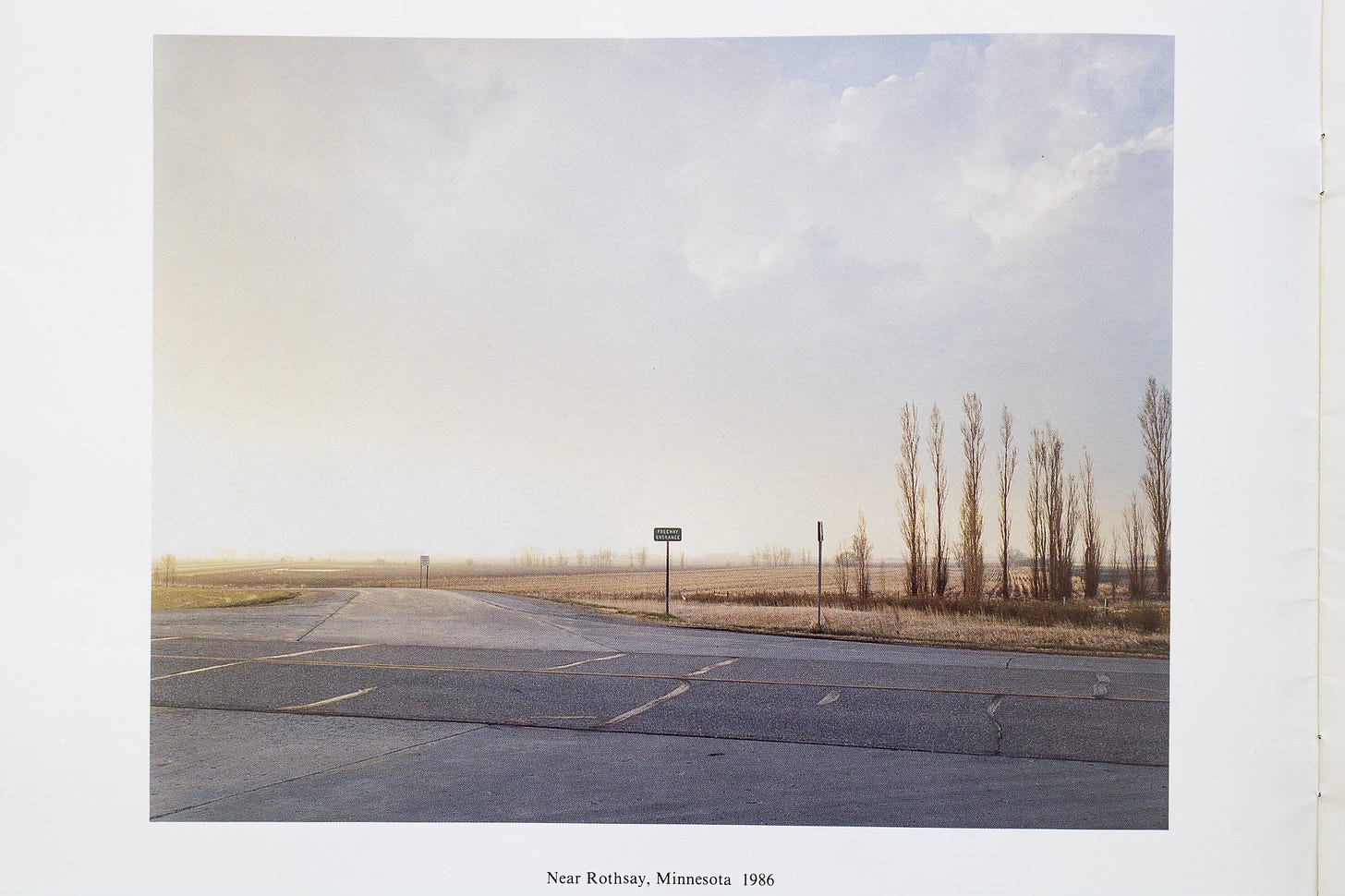

This essay is primarily about a single image, which you can see below. It’s from an exhibition catalog Photographs David McMillion. The exhibition took place at the Gallery 1.1.1. School of Art, University of Manitoba October 21 - November 10 1987.

There is a photograph by David McMillan: a quiet roadside with a “Freeway Entrance” sign, where the main road dips away toward an unseen highway framed by a thin line of winter trees on the right. The sky is in transition, gray to the left, but with clearing light and bright cloud banks forming on the right. Nothing dramatic announces itself, and yet the longer I stay with the picture, the more the scene settles in. The road isn’t newly paved, but it’s not crumbling either. There seems to have been some repair work, which seems like indecision made manifest.

The trees hold still. The composition doesn’t call for your attention, at least not immediately. But if you linger, the scene begins to open: the gentle decline of the pavement, the slight asymmetry of the signage, the subdued way the light reaches and touches the ground. There’s no story here, no dramatic claim. But every road gets your mind creating a narrative. This way the image holds you. It lets you register how this place remains intact, not through beauty or symbolism, but through endurance.

This kind of photographic attention, both steady and unforced, is one of the reasons McMillan’s work, for me, calls to mind John Gossage’s The Pond. First published in 1985, the book walks us through a patch of wooded land on the edge of Washington, D.C., following a strange non-narrative path that seems to go nowhere except where it started. Gossage photographs gravel, wires, pond scum, litter, circling birds, broken branches. The materials are everyday, in this case, often discarded things, even ugly. And yet the tone isn’t ironic, despite what some early readers assumed. The echo of Thoreau in the book’s title led a few critics to expect satire, a critique of ruined landscapes disguised as nature. The photographer Robert Adams saw through that. He wrote that Gossage’s images were memorable "because of the intense fondness he shows for the remains of the natural world." The photographs include signs of damage and neglect, but they aren’t judgments. They could be called “recognitions.”

Here McMillan’s photograph work the same way. He doesn’t ignore what has gone wrong in the landscape, poor drainage, decay, minor vandalism, but he doesn’t organize the frame around that message either. The surface is fully visible, evenly lit, and the composition gives it room to be seen. His camera doesn’t explain why this place matters. Why any of these commonly experienced places matter. It simply presents them in a sense "truthfully."

Robert Adams wrote that the best photographs describe "a natural beauty that implies a higher order, but does not make its way plain." In other words, there is a refusal to simplify, either into beauty or despair, this is part of what gives this kind of photography its quiet force. Gossage ( in The Pond) doesn’t isolate what is pleasing or unusual. He just includes what’s there. Here, McMillan does the same.

Frank Gohlke gives us the clearest language for this approach. From reading my understanding is he and McMillan worked closely for many years. Gohlke’s own photographs of grain elevators, riverbanks, and the edges of urban infrastructure share a similar refusal to speculate. There is no guessing. Like McMillian, his images seem documentary, and documentary photos avoid speculation. He wrote about the importance of "intense scrutiny," by which he meant not close-up seeing, but returning again and again until relationships within a place begin to show themselves. For Gohlke, meaning wasn’t captured in a moment, it was revealed through repetition, patience, and accumulated familiarity. I know this is a tough thing to make clear to people who want to know why I've gone back somewhere for the fifth or sixth time.

That’s the sense you get from McMillan’s work. These photographs don’t look like they were made in a single pass. They feel like the result of walking through a place more than once, maybe a dozen times, and only lifting the camera when something quiet fell into place. The details in these images are clear. You can make out the difference between wet concrete and dry, where this year a road repair was made, and over there where there was a road repair a few years back. These photographs don’t ask to be admired, but still they hold your attention with details about what has happened here. It gives you time.

That level of visual detail, without visual drama, is part of what makes people ask whether McMillan used an 8×10 camera. I haven’t found confirmation, but the prints suggest that kind of slow working precision and a sense of light I often notice in larger cameras. Or with people who make the time to experience a place. This is not because these images are sharp in a clinical sense, but because every texture is stable, every tonal transition measured. In the exhibit catalog photos you can see the grain of wood, the rust on a chain-link fence, the way light sits across a sidewalk without flaring or flattening. And in spite of this, these images don’t call attention to themselves. They just hold steady and let you notice.

There is a kind of reverence in that. Not in the religious sense, and not in the romantic sense either. Reverence here means letting the world be seen without correction. It means staying long enough for the ordinary to become sufficient, then significant. Not because it reveals a grand design, but because it reveals itself at all. You are a bit surprised, this was unexpected, but welcomed. Gossage photographs pond scum and finds in it the same attention he gives to a bird in flight. Gohlke photographed the same grain elevator dozens of times, not to pin it down, but to understand what it was doing after being planted there. McMillan, in his images, seems to believe that if you don’t rush, if you don’t reach too soon for interpretation, the photograph will take on weight.

This is not passive work. It takes a different kind of discipline. It asks the photographer to step back and let the subject exist on its own terms. It also asks the viewer to slow down. As Frank Gohlke put it, this kind of image “does not surrender its meaning all at once,” but invites “repeated looking.” It’s not a calendar photo you count the days to see next month’s. He believed a photographer must “return again and again” to a place, not to tame it, but to earn its presence. For Gohlke, that practice was ethical: the camera should not impose a narrative but allow the place to speak slowly.

Robert Adams echoed this restraint when he wrote that good pictures arise from “a kind of moral realism,” one that sees clearly, but without domination. He reminded us that even the act of photographing could be a gesture of care, so long as it was offered without control. “We live in the middle acts,” Adams said, not innocent, not redeemed, and art should help us endure that ambiguity. A true literature major.

Gerry Badger, in his essay The Quiet Photograph, argued that this work is not emotionally neutral, but deliberately quiet in order to respect complexity. Quiet photographs, he wrote, are “not trying to shout over the noise of the world,” but are instead engaged in “a kind of democratic attentiveness.” They wait, rather than declare.

McMillan’s images belong to this lineage. Their quiet is not indecision. It is what Gohlke called “intense scrutiny,” and what Adams called “a form of responsibility.”

That’s what I value most in McMillan’s photographs. They don’t press. They wait. They don’t flatter the landscape, but they don’t abandon it either. They allow for time, imperfection, and small evidence. And they remind me that attention, when offered without demand, is a kind of care.

CODA

As I wrote above, it's difficult to find any of these old colour photos by McMillon. I had to locate a copy of an exhibit catalog from decades ago...in another country, and purchase it. You are lucky, you can just look and read about his more recent work about Chernobyl at the site listed below. Those images, which I had lost track of in my mind, are startling in their simplicity, beauty and sense of pathos. Take a look. And if you find a resource for seeing these earlier works….write me!

References

Adams, Robert. “On John Gossage’s The Pond.” In Creative Camera: Thirty Years of Writing, ed. David Brittain. Manchester University Press, 2000.

Adams, Robert. Beauty in Photography: Essays in Defence of Traditional Values. Aperture, 1981.

Baillargeon, Claude. “Growth and Decay: Pripyat and the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.” Border Crossings, Issue 150, 2019.

Badger, Gerry. “The Quiet Photograph.” In The Pleasures of Good Photographs. Aperture, 2010.

Gohlke, Frank. Thoughts on Landscape: Collected Writings and Interviews. Hol Art Books, 2009.

Gossage, John. The Pond. Aperture, 2010. With essays by Gerry Badger and Toby Jurovics.

McMillan, David. Growth and Decay: Pripyat and the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Steidl, 2019.

Atomic Photographers Guild. David McMillan. (https://atomicphotographersguild.org/members/david-mcmillan)

______________________________________________________

You can help me maintain this site by simply sharing it with friends, subscribing, and restacking it. These things allow us grow an audience and a community.

Another great essay, Jim! I admire your writing, your ability to dissect a topic and write about it. I can see all these influences in your own photography. I was not familiar with David McMillan but the photograph you chose for your essay speaks to me. Thank you for sharing!

A thought-provoking essay, one that makes me want to linger on images more. "The trees hold still. The composition doesn’t call for your attention, at least not immediately. But if you linger, the scene begins to open."