Photo Jim Roche 2025

Lately, I’ve been thinking about what I find hard to explain or describe. In one sense, what I’m thinking about is skill. In another quality or maybe range, fluency. As an artist, sometimes how good you are at something is revealed in how fluently you can do it. Like playing an instrument, or I’m reminded of Joan Mitchell, the painter, talking about applying paint. Knowing exactly which brush and having exactly the right viscosity. Then there’s a singer’s range of notes, what they can hit, how high, how low. There is so much pop music these days more focused on providing a singer an opportunity to demonstrate their range, that there seems to be no space left for anything else.

Photo Jim Roche 2025

I remember, as a kid, watching the Ed Sullivan show. A pianist or violinist would play something really, really fast….and that was all you would remember. There were also people spinning plates on tall sticks, and jugglers juggling two, four, eight, nine ten balls! Violinists often get caught up in this, or should I say, observers of violinists. Not people who play the violin, but those who listen to and watch someone else play the violin - fast. There are so many videos on YouTube of people playing a violin fast, usually an “electric violin.” We can all be impressed when someone plays very quickly or sings impossibly high, even when, deep down, the performance doesn't succeed in moving us at all. You usually end up with something that…well, if you understand music, isn’t really good music. Slowing the music down, you notice missed notes….off key…empty and purposeless.

In Catechism class, I won the award for saying the Hail Mary ten times. not just ten times but faster than any other kid in class could. They lined us up, and Sister Bertrice stood with a stopwatch and marked the time next to each student’s name on the board. I won a plastic Virgin Mary, which glowed in the dark. It was that odd translucent white plastic, except for Mary’s dark blue robe. I would take it and step into the closet, shutting out the light, watch the glow and wonder how this could be? Hail Mary! Later that weekend, at the Bijou Theatre, I stood in line to watch some Roman war movie and The Three Stooges Go To Mars. (OK, maybe it was Abbot and Costello.) The good Sister walked down the line and slapped every student from her class on the face for watching such “garbage.” The power of speed and the glory of the win didn’t last as long as I hoped.

In photography, this fascination with esoteric skills often shows up in how many gradations of grey you can reproduce. Ansel Adams made a big deal of this. He developed a system for exposure and printing as wide a range of greys as possible and wrote an entire book about it. But if you look at a lot of more modern Japanese photography, you just aren’t going to see too much emphasis on that particular skill. When they say black and white, they, seriously, mean it. To many people who shoot in colour, the skill seems to be how well you can manipulate the image in Lightroom or Photoshop. We see landscapes with remarkable colour and lighting….it’s a show of force, skill and…..talent. “He’s such a good photographer!”

Photo Jim Roche 2025

Online, we celebrate the technical: That’s a "perfect composition," those "amazing colours," and how "breathtaking" an image might be. “How did you get that shot?” Usually, they didn’t, they invented it. But increasingly, I find myself wondering: where is the feeling? The atmosphere? The humanity? What’s the purpose? Where is the substance? If I see a zine, book or webpage of one of these photographers’ images, or flip through the pages of a photo magazine at the bookstore, I find that these kinds of perfectly constructed images quickly become boring, and I put the magazine back in the pile, click through the webpage or return the book to the library shelf.

Iceberg by Caspar David Friedrich

But the praise is loud! Online, the word in the comment threads that bothers me the most is “sublime." Even when my high school friends and old workmates post a vacation image, someone will write, “it’s sublime!” Sublime gets tossed around like a default compliment, detached from what the sublime is. It’s not about technical skills or visual perfection. The sublime is about a sense of beauty tinged with danger and fragility. A sense of unease. It’s about standing at the edge of a cliff, stunned by the view, but more importantly, being aware that a wrong step could be a grave mistake. Yes, there is a sense of awe, which many people seek by playing fast, being loud, extending their range and adding a lot of colour. But the sense of awe needs to come with a bit of anxiety attached, which is usually missing. Many artists, no matter what they do, are afraid to make the listener, reader or viewer uncomfortable. I was thinking the other day that the problem is the way we use the term sublime. We say it’s a “sublime” painting or photo, but we should be looking for a painting or photo of the sublime. The thing being viewed is seldom the thing being viewed. It’s seldom the subject of the image. It’s something about the subject we feel.

The Lightning Field, an image, and place I experience “the sublime.”

There is a conceptual earthwork I was shown around 1977 called The Lightning Field. It’s a documentary photograph of a conceptual art project. It is not Ansel Adams. The Lightning Field is an earthwork by the American sculptor Walter De Maria. A work of Land Art situated in a remote area of the high desert of western New Mexico. There are photos of the field on sunny days and rainy days. Photos where nothing is happening, and some photos of lightning lighting up the night sky.

For the landscape photographer, you realize the land is not the setting for the work but a part of the work. When I see it, I feel a sense of awe…even on a sunny, quiet day, I feel the danger of the sky and earth coming together to clash. I don’t think this piece is about the moment of the lightning strike. If you go there, it’s unlikely you will experience lightning. But the work itself, in the land, under the sky, can consume you. In your mind, it is not just what you see on those quiet sunny days, but what was or could be. That’s where the sense of awe is. It’s behind what you're looking at.

When I was a kid, growing up on the East Coast, lightning storms were a kind of theatre. As soon as the first crash was heard, my mother would run around the house, closing windows. She was convinced the lightning would come in, through the windows, and kill us all. After closing the windows, she'd sprinkle holy water over everything and everyone. She was fast and urgent. Personally, I always thought the holy water should come first, then the window. But it was her ritual. A way to manage what couldn’t be handled. A way to survive the awe of nature. When I hear the thunder and see the lightning, all of these thoughts go through my mind. Shut the windows! Sprinkle the Holy Water!

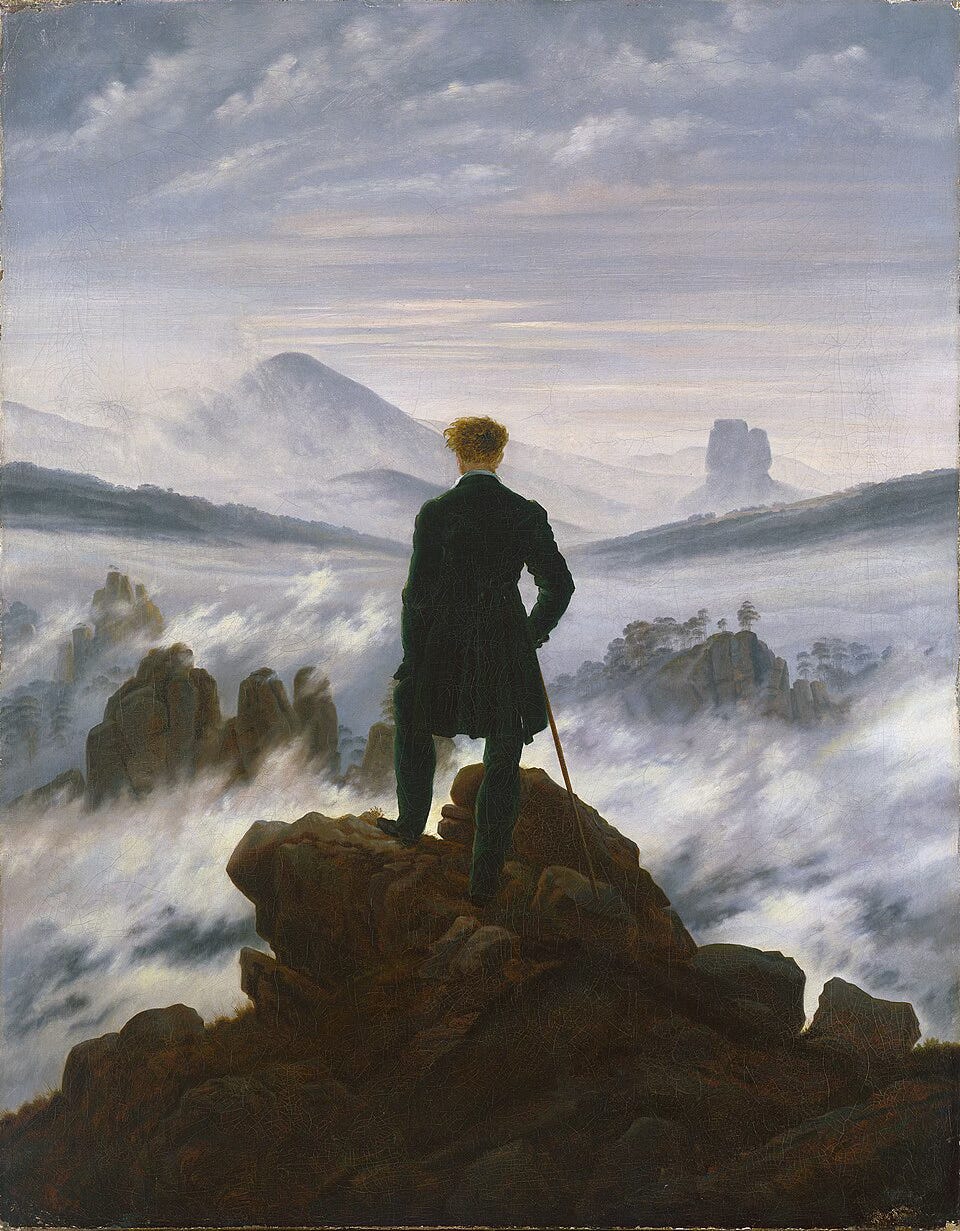

CDF: The Wanderer Above A Sea of Fog. It’s not the beauty that he is looking at; it’s the unknown. The endless danger.

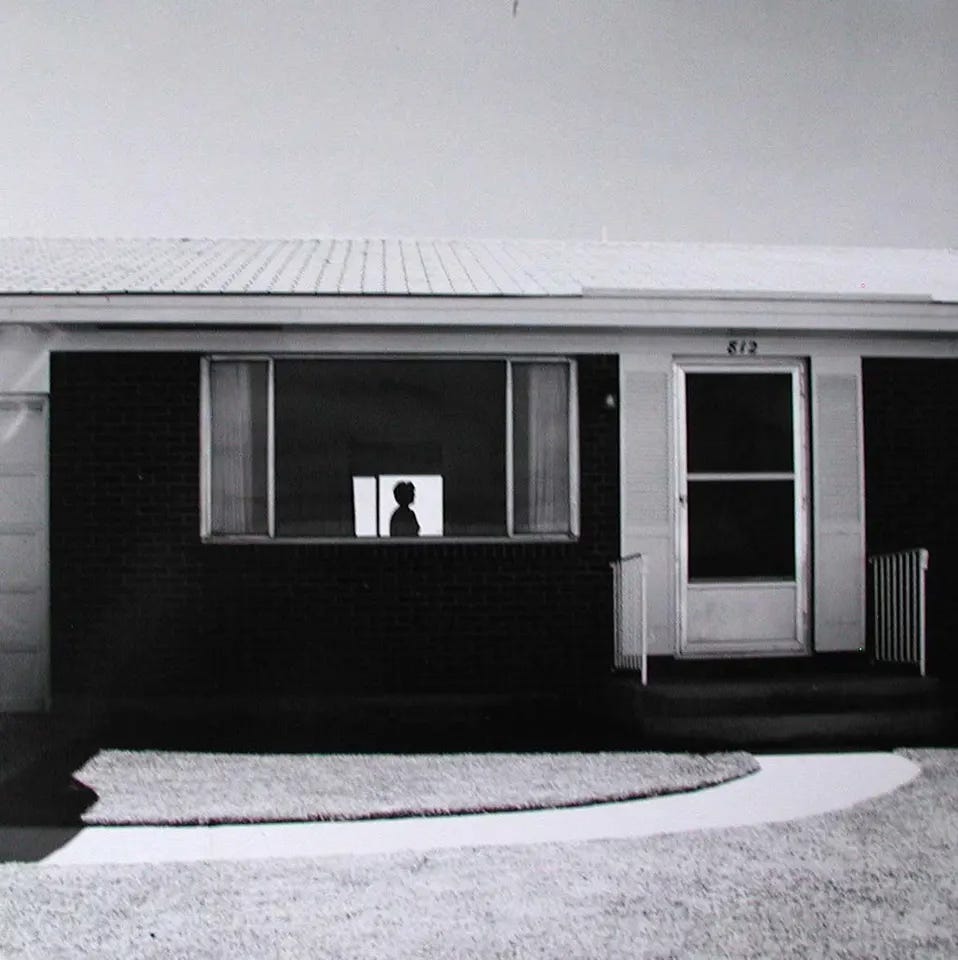

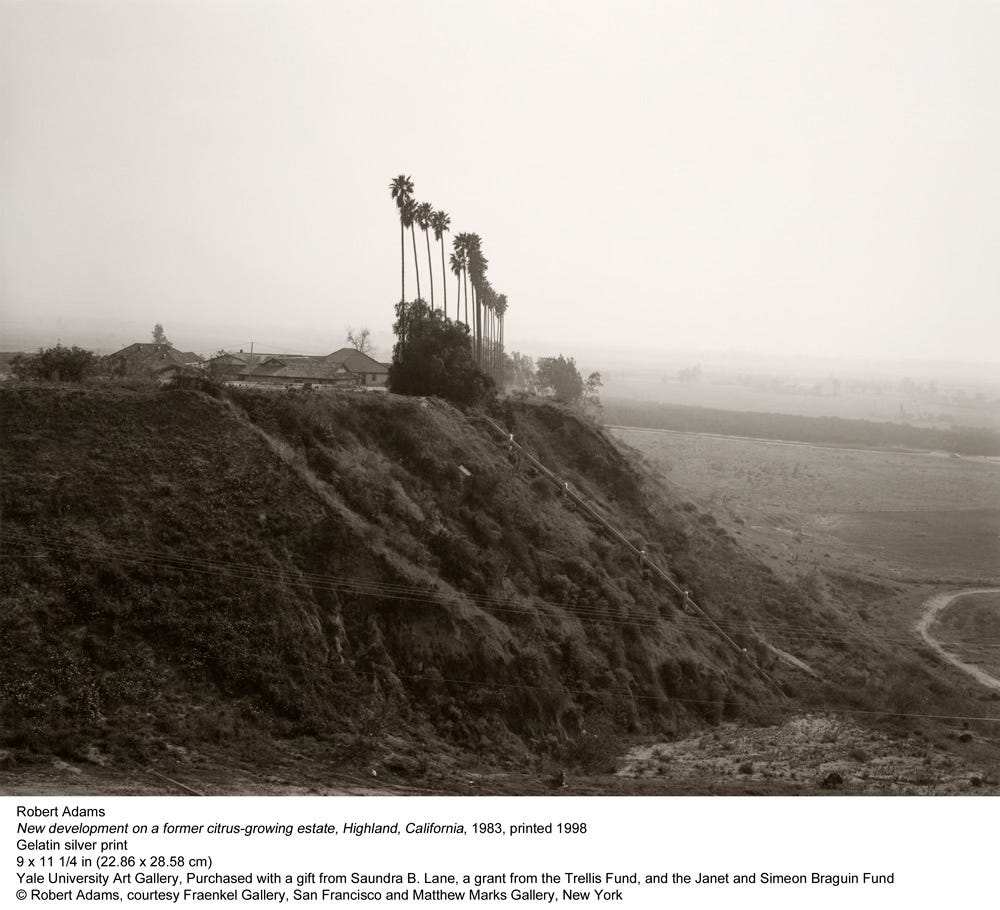

That uneasy feeling of being small and exposed makes the sublime powerful. It often shows up in simple things. In a photograph of an empty road or a cluster of cottonwood trees in Robert Adams’ work. These are photos that don’t shout, but murmur. While technically these are perfect prints, you overlook that. Adam’s photos often whisper horrible things about destruction, unwanted change, isolation, and loss. You will see their unspeakable truth if you stare long enough into their silence.

Robert Adams, Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1968

Another place that “sublime” would be appropriate.

gelatin silver printAll of this is surprisingly accomplished through details of little apparent significance. In so many of my photographs of pathways, the fact that nothing of importance seems to be happening becomes disturbing. It feels like an absence loaded with memory.

Two more examples: I felt that same feeling the first time I watched the movie The Unbearable Lightness of Being, which is a 1984 novel by Milan Kundera about two women, two men, a dog, and their lives in the 1968 Prague Spring period of Czechoslovak history. Kundera’s idea is that our lives are weightless and irretrievable. Life slips by, and it’s best just to let it go. Life is awe-inspiring, but if you spend too much effort holding on, you lose its meaning. Life, a good life, is like a quiet photograph. But something is disturbing in that it can suddenly simply float away. If you try to hold on, you’ll waste your time. If you have watched the movie, I suspect you, too, might wonder, when it suddenly comes to an end, “what am I supposed to do?”

Photo Jim Roche 2025

Early Morning Before the Rain

In response to these thoughts, this past week I rearranged what music is on my iPhone to listen to while I walk. One song is very quiet, but powerful: R.E.M.’s "Nightswimming." It’s so restrained, so delicate. The lyrics speak of memory, intimacy, and loss. There's nothing flashy in it. No showing off. No demonstration of how high, loud or quickly the vocalist, Michael Stipe, can do this song. It’s of a purposely limited range. But it’s sublime, in the original sense: beautiful, fleeting, dangerous, and scary. That “photograph on the dashboard.” That September moon. The fear of being seen naked. The feeling of something once reckless is now gone. Even the loss of fear is something that reminds you of your limitations. Your humanity. (There is a link below to listen to this song, to me a perfect song, like a poem, that uses a minimum of tools to get its point across. I would use the word elegant.)

Sometimes, when driving away to take images somewhere, I play this song and think about that “photograph on the dashboard,” just a snapshot facing the wrong way so the driver can see its reflection. I think, “I want to take that photograph today.”

All this reminds me of something Dave Hickey wrote in his essay "The Delicacy of Rock-and-Roll." He describes pop love songs, which he wrote several of, as fragile gestures, teetering between cliche and revelation, easily ruined by insincerity. Hickey argued that writing a love song isn’t about polish; it’s about risk. The risk of being honest. The risk of being too open, too sincere, too easily dismissed. And that’s why he thought they (love songs), are as silly as they can be, like snapshots instead of formal portraits, but powerful. Because they dare to be fragile.

The sublime in art comes from that tension between attraction and fear, beauty and vulnerability. In Robert Adams’ work, quiet songs like Nightswimming, Hickey’s writing and love songs, and the movie about the lightness of being, the sublime isn’t an immense feeling—it’s a small, trembling one—the one that reminds you of what you’re seeing, hearing, or remembering.

The art that matters is the art that lets the holy water spill a little. It lets you feel the storm without shutting all the windows. It reminds you you’re alive and not in control. When it comes, that beauty comes on tiptoes and doesn’t stay long. Take out your camera and pay attention.

Lyrics

Nightswimming deserves a quiet night

The photograph on the dashboard, taken years ago

Turned around backwards so the windshield shows

Every streetlight reveals the picture in reverse

Still, it's so much clearer

I forgot my shirt at the water's edge

The moon is low tonight

Nightswimming deserves a quiet night

I'm not sure all these people understand

It's not like years ago

The fear of getting caught

Of recklessness and water

They cannot see me naked

These things, they go away

Replaced by everyday

Nightswimming, remembering that night

September's coming soon

I'm pining for the moon

And what if there were two

Side by side in orbit

Around the fairest sun?

That bright, tight forever drum

Could not describe nightswimming

You, I thought I knew you

You, I cannot judge

You, I thought you knew me

This one laughing quietly underneath my breath

Nightswimming

The most helpful thing you can do is a small thing, restack my essay(s). Your help is really appreciated. You can view my photography at www.jimroche.ca

A video of Nightswimming.

Nightswimming is great.

And technically excellent images can move a person, but most often they don’t.

Move people in whatever way you can. Thats my advice. You did that here, I am certain.

Sublime :)

Seriously, a profound and compelling essay, Jim!

There are a lot of words people use to describe art that really don’t mean much. “Sublime” is just a way of saying “great” — a fancy thumbs up.

Artists write how their work is “liminal” and they only mean “somewhat complex.” Folks who are “deconstructing” are usually just asking questions. As with “sublime,” the original meaning and usage of these words was quite interesting, but now they have become empty cliches.

Thanks for working to resuscitate “sublime,” which is a wonderful concept.