An Objectively Enjoyable Conversation

Notes on Objective Photography

The plates were cleared, though a bowl of pears from the tree in the back yard lingered on the table. Wine glasses and tumblers caught the lamplight, a soft light that seemed to actually darken what it touched. The host, whom we will simply call The Photographer, twirled ice around his tumbler while thinking about a photo of a glass with green mint leaves in it taken by Rinko Kawaguchi. On one wall, books lined the shelves; above them, leaning in a row, were framed photographs from the Photographer’s latest series, compost piles, heaps of stalks, leaves and peelings, and close-ups of leaves, flowers, and a few apples past their due dates.

The Critic stood before the largest framed photo.

“So this is your subject? A heap of garbage?”

“Not garbage, compost,” the Photographer said. “Even waste has dignity if you wait long enough.”

There was laughter.

“Careful,” said the Teacher, smiling. “Don’t become Alcibiades so soon. We’re here for dialogue, not conquest.”

“Then let me be Alcibiades tonight,” the Critic replied. “Someone must keep you all honest.”

The conversation began.

“The problem with your work,” the Critic said, tapping the frame of the compost photograph, “ is that it’s too… plain. It defines vernacular. No shimmer, no metaphor, if there is allegory, it’s lost to me; there is no space for imagination.”

The Photographer: “You know I use ‘objective’ to describe how I work,” he answered. “Tripod steady, no staging, no tricks. Objectivity is a method, not a meaning. The picture may still carry feeling, emotion, maybe even mystery but I won’t decorate it into drama.”

The Poet reached for Louise Glück’s Ararat in the bookshelf.

She directed her comments first to the critic, then to everyone. “You know, Glück was told the same. When she stripped away metaphor, critics called her barren. Think, calling a woman barren. They said she was now heartless. She wrote, ‘I was wounded. I lived to revenge myself against my father, not for what he was - for what I was, from the beginning.’ That’s done best with plain words, no shimmer. No one who hears or reads her words doubts their pain.”

“But is that poetry?” the Critic asked, “Or just confession?” Can you tell me the difference?

“It is dialogue,” the Poet said. “She called her new poems: refrigerator poems, “ poems that preserve what would otherwise rot.” Is that not what your compost does, too?” she said, turning to the Photographer.

As a group we laughed again, softly.

At that moment, Robert Adams, silver-haired, entered the conversation with a thin volume under his arm: “The other night, you quoted me correctly,” he said. “I never believed in photographic objectivity. Every picture is a choice. Where to stand, what to leave out, what to honour with light. But to claim neutrality is to deny responsibility.”

The Critic flipped through the Photographer’s copy of Beauty in Photography. “Sometimes your ideas are as thin as your books, Robert!”

“Better thin than padded,” Adams smiled. “A photograph has to be concise; why not a book?”

“Glück would agree,” said the Poet. “She cut until only bone was left. Isn’t that what bothers some of you about these photos? The editing…. It clarifies, but forces you to work more precisely. No loose ends to misuse.”

“And bone carries marrow,” said the Teacher. “At least no one called her an objectionable objectivist, eh?” A few low chuckles.

“But Robert,” the photographer said, “when I call myself objective, I mean something narrower. Not neutrality, but disciplined. A way of working. like using priority aperture, or a tripod, not a claim about what the picture finally means.”

He paused and then went on, “I try to remove myself from the process. I trust the viewer to take up the job of finishing the development process.”

The Teacher reached for Jane Jacobs’s The Nature of Economies on the bookshelf. “Jacobs wrote, ‘Development isn’t a collection of things but rather a process that yields things.’ Perhaps objectivity is like that. Not an end state, but a process, a guide.” He thought for a moment more and then went on, “Robert’s right about responsibility…but it’s the responsibility of the viewer to put some effort into finishing the encounter.”

Adams paused. “About discipline, perhaps. But words can mislead. If you mean discipline, then yes, I accept that. But with art there is also responsibility, on both parties’ part.” “Where is Jacobs anyway?”

The critic answered, “You did read about it? She behaved poorly in court and was sent home for the day like an unruly child.”

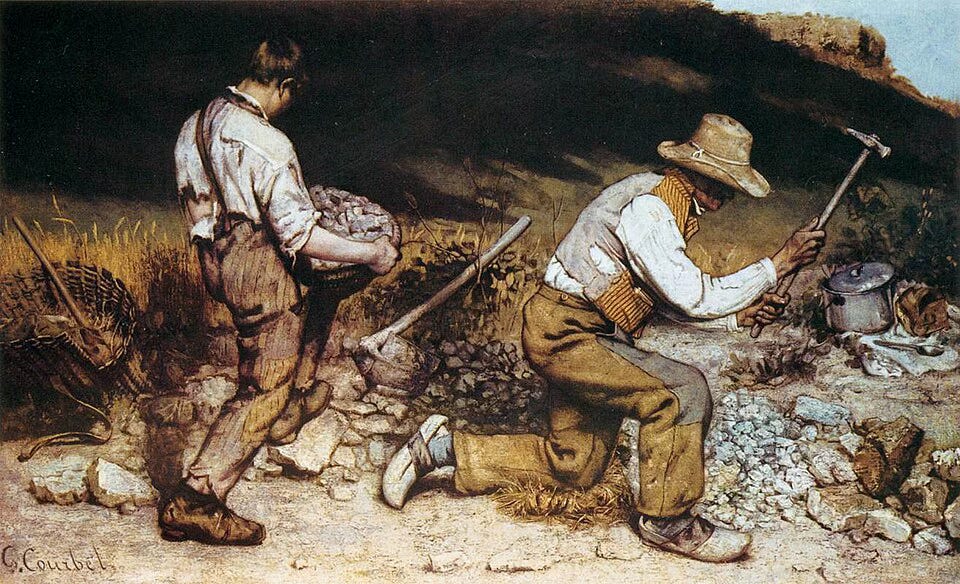

The Painter lifted a volume of reproductions. “Let’s get back to basics. Look at Millet’s The Stone Breakers. I’m sorry, Courbet, Courbet. My art history class was 50 years ago, but the image was the first painting they showed us in class. Two men bent to labour. No allegory. No angels. Just toil. Once this work was called ugly, now it’s called honest. Plainness became dignity.”

“At least Courbet gave his stone breakers politics,” the Critic said. “Millet risked sentimentality. Watch who you confuse with whom.”

“Yet the truth of stone and bent backs remains,” the Painter answered. He turned another page. “Or think of Turner, the romantic fog master? Look at this, he turned the book of images as if telling an entire story, The Fighting Temeraire, dissolving into light. And then, bottom right, a tiny red buoy, added at the last moment. Not metaphor, just a navigational fact.”

“Surely the buoy must symbolize something, blood, fate, a warning!” the Critic declared.

“Or perhaps Turner just saw a buoy,” said the Painter. “Not every red dot is a metaphor.”

Even Adams chuckled. “Well, some people say I photograph metaphors, but I guess I reject that too.”

The Poet read from a small Japanese volume. “Bashō: ‘First winter rain - even the monkey seems to want a raincoat.’”

“That’s just description,” the Critic said. “A monkey, a coat, a shower.”

“And yet you feel the ache, don’t you?” the Poet asked. “Or this by Issa: ‘This dewdrop world is a dewdrop world, and yet, and yet…’ Nothing but description. And yet!”

“Then plainness does not block imagination,” said the Teacher. “It provokes it. We have made our first important discovery for the night, before the second bottle of wine was even opened!”

The Critic looked up again at the compost heap. “It is still garbage.”

“It is compost,” the photographer said. “Time visible. What dies feeds what comes. If that isn’t mono no aware, what is?” Sorry, I say objective about the image I give you, the metaphor is your job. Get to work. I will, however, admit to deep feelings of loss when looking at a compost pile.”

“Yes,” the Poet added. “Sadness, but also renewal. It’s a dialogue between decay and growth.”

“Plain, yes,” said Adams. “But not void. Truthful. And in truth, there is always hope.”

“Critic,” the Photographer said, “since you’ve been Alcibiades all evening, will you do us the honour of summing up what we’ve said?”

“I’d of course be more than happy to sum up what you said…,” the Critic replied, grinning but serious. “We began with a heap of compost, which I called garbage, but others felt led to enlightenment of some sort, which had some relationship to rain, and monkeys wearing raincoats. I brutally accused your photographs of plainness. The Poet showed us that plainness can still cut - Glück’s wounds, and we were all agreed, after drinking a great deal, that editing is important, but apparently knowing what path you're on at the start increases the likelihood of your arrival.

The Painter spoke: “Well, when I think of Turner, where even a red buoy in fog is not necessarily a metaphor. That makes me question a lot about intentions. But even Adams told us objectivity cannot be an end, that truthfulness must guide. And the Teacher reminded us that guides, not absolutes, are what matter. So… perhaps plainness is not emptiness after all, but the discipline that lets feeling appear. I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to step on your toes there…”

“A fair summation,” Adams nodded.

“And well spoken,” said the Poet, “for Alcibiades.”

The Teacher raised a glass. “To compost, to buoys, to bone and marrow, and to an objectively enjoyable conversation.”

Notes on Form

This dialogue is written in the spirit of the Socratic dialogues. In ancient Athens, Plato recorded conversations in which Socrates led his companions to question their assumptions through patient inquiry, playful challenges, and irony. The method was not about delivering a final doctrine but about testing ideas together, locating truth through back-and-forth conversation rather than proclamation.

The form has been borrowed by Cicero’s in Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, and by Jane Jacobs’s in her tiny book The Nature of Economies. It remains useful because it shows thought in motion: ideas emerging not from solitary declaration but from dialogue, dissent, and discovery. In law school, this is how we learned, but you can also learn this way in grade 1. In a world where arguments often turn extreme or absolute, Socratic conversation reminds us that understanding comes through conversation, patience, and humility. Next time, back to discussing photography and art between us.

The best thing you can do to help me out is share these essays, re-stack them, make comments and subscribe.

What a great read! Such fun to imagine that this conversation took place. I want to have been there, with a good glass of vino, of course.